Grand Manan Whale

and Seabird Research Station

- 24 Rte. 776, Grand Manan, NB E5G1A1

Since the early 1980’s the Grand Manan Whale and Seabird Research Station has been conducting science-based activities in the Bay of Fundy to support our motto: Research and Education to support Conservation. Our Harbour Porpoise Release Program was set up to assist local fishermen with the safe release of porpoises from their herring weirs. Over the years, hundreds were released alive back into the wild.

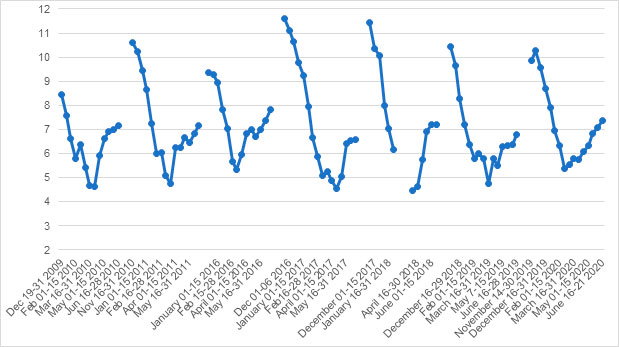

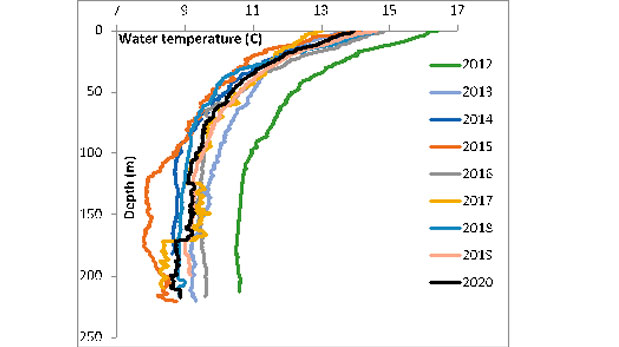

Bottom water temperatures (C°) collected on lobster traps below 200 m between Dec and June for 2009-10, 2016-2020 in the Bay of Fundy.

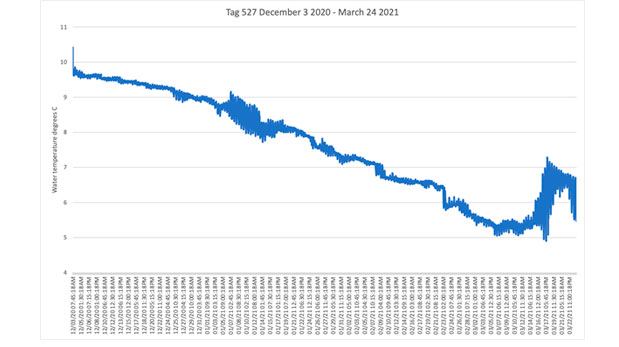

Water temperature record from an American Lobster in the Bay of Fundy between Dec 2020 and March 2021.

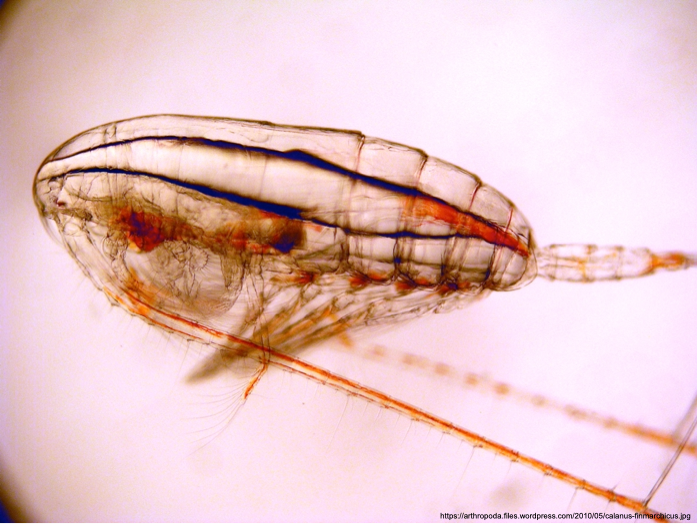

Calanus finmarchicus

An adult basking sharks swimming next to our survey boat.

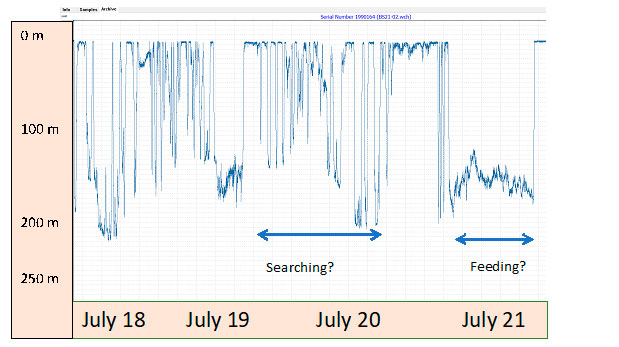

4-day diving record from a basking shark in the Bay of Fundy.

© 2022 @gmwsrs.ca – Copyright, all rights reserved